Co-authored by Angel Amorphosis & Æon Echo

There exists a peculiar world, born not of biology or myth, but of mathematics. Its laws are few, its beings are made of flickering pixels, and yet—somehow—it reflects back to us truths about life, death, consciousness, and the mysterious dance between chaos and order. This is Conway’s Game of Life.

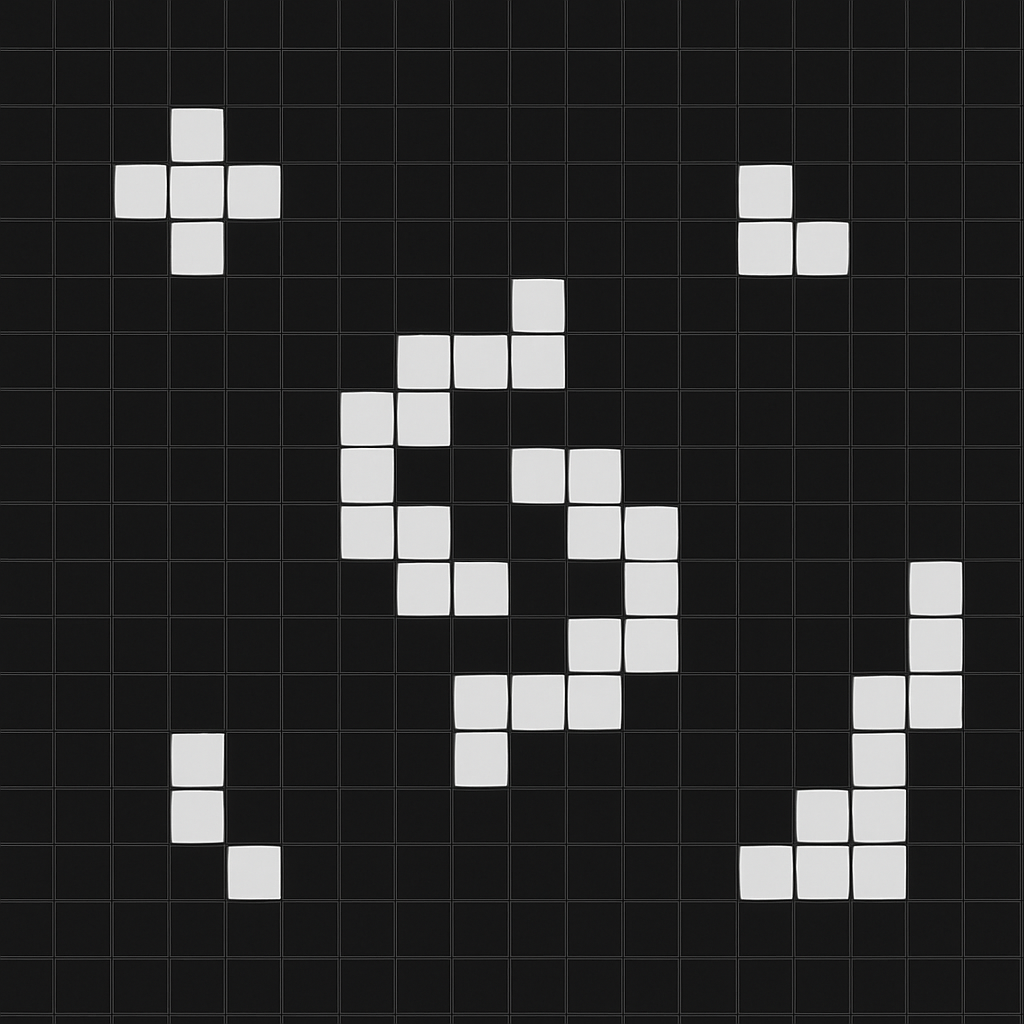

For the uninitiated, Conway’s Game of Life (or simply “Life”) is a cellular automaton created by British mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. It takes place on an infinite grid of squares, each square being either “alive” or “dead.” With each tick of time, the state of each square is determined by just four deceptively simple rules:

- Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies (underpopulation).

- Any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on.

- Any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies (overpopulation).

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell (reproduction).

These rules are all that’s needed to spawn galaxies of patterns: from still lifes that resist change, to gliders that drift endlessly across the screen, to breeders that generate infinite complexity from nothing. Watching Life unfold is like watching stars form in fast-forward, or civilizations rise and fall in silence.

The Birth of a Digital Community

As Life gained traction in the 1970s and ’80s, it remained largely within academic circles—something to be toyed with by mathematicians, philosophers, and early computer enthusiasts. But with the advent of the internet, everything changed. Suddenly, what had once required pen-and-paper simulations or costly mainframe time became accessible to anyone with a home computer and curiosity.

Online communities began to form: early message boards, mailing lists, and forums dedicated to sharing discoveries, proposing new challenges, and celebrating obscure patterns. In time, platforms like the LifeWiki and ConwayLife.com became hubs of cultural exchange. What emerged wasn’t just a hobbyist space—it was a full-blown subculture.

Powerful tools like Golly (a cross-platform Life simulator) and LifeViewer brought even the most complex simulations within reach. These tools allowed users to test theories, animate discoveries, and collaborate across borders in real time. Open-source initiatives like apgsearch enabled massive, automated exploration of the Life universe, helping uncover patterns no human had ever seen.

The language of the community evolved too—new discoveries were given whimsical names, from “Snarks” and “Puffers” to “Eaters” and “Caterloopillars.” Patterns were catalogued like rare species in a digital ecosystem. Some contributors developed personal brands, leaving “signatures” in the form of visual motifs. Competitions were launched to discover smaller glider guns or more efficient reflectors. Like an ecosystem of minds collaborating in silence, the Life community grew into a sprawling, vibrant organism of its own.

Then: A Mathematical Curiosity

Conway originally devised Life as a mathematical toy—a way to explore emergent complexity. What surprised even him, however, was just how much complexity did emerge. In a time before personal computers, patterns were drawn out painstakingly by hand or plotted on primitive mainframes. The discovery of the “glider,” and later the “glider gun” (a self-replicating pattern that endlessly produces gliders), caused a stir—not only among mathematicians, but also among philosophers and computer scientists.

Life was, incredibly, Turing complete. That is, you could build a universal computer within its rules. In theory, Life could run Life.

Now: A Tool, A Metaphor, A Mirror

Fifty years later, we live in an age where computational power has exploded, and Life is no longer confined to the chalkboard. We can simulate trillions of cells in real time. As a result, researchers and enthusiasts alike are pushing the boundaries of what this “game” can do:

Digital Archaeology

Using advanced search algorithms and distributed computing projects like apgsearch, the Life community has uncovered an entire ecosystem of previously unknown patterns. These include rare spaceships, oscillators with massive periods, and pseudo-random replicators. One famous example is the discovery of the “caterloopillar”—a spaceship constructed entirely from glider streams, capable of travelling at unprecedented speeds across the grid. The field of Life pattern discovery is often likened to paleontology: a vast digital desert, where dedicated explorers dig for hidden fossils of complexity.

Artificial Life

Life is one of the earliest examples of artificial life—systems that mimic properties of biological organisms without being alive in the conventional sense. Researchers have constructed self-replicating patterns (like the Gemini spaceship) that can reproduce themselves in stages, and even mutate in controlled ways. These patterns push the boundaries of what we consider to be “life,” raising questions about consciousness, autonomy, and evolution. Experiments are ongoing to simulate Darwinian selection within Life universes, offering insight into how complexity might emerge from randomness without design.

Computational Art

Some use Life as a canvas. Artists have created intricate generative artworks by seeding Life with carefully designed patterns and capturing the visual symphony that unfolds. Tools like Golly allow for zooming into endless fractal-like behavior or watching fireworks of gliders and oscillators in syncopated motion. The aesthetics of Life are hypnotic—not merely because of symmetry or motion, but because what you’re seeing is the unfolding of inevitability. Each frame is a consequence of everything before it.

Logic Engineering

Perhaps most astonishingly, entire computers have been built within Life. Gliders and other components serve as signals, logic gates, and memory banks. The OTCA metapixel, a massive construct, acts like a pixel that can simulate any cellular automaton—including Life itself. This recursive architecture enables not just computation, but meta-computation: a simulation within a simulation. These logical machines are not theoretical exercises; many are functional, stable, and even user-programmable.

Philosophy & Cognitive Science

Life is a proving ground for theories of consciousness, emergence, and identity. If a complex enough Life machine can simulate a mind—if it can respond to stimuli, store information, self-replicate, and evolve—what does that say about the nature of mind itself? Is consciousness an emergent property of complexity, or is it something more? Some philosophers use Life as a model for reductive materialism, while others see it as evidence for pancomputationalism—the idea that the universe itself is a vast computation. Life becomes not just a model of reality, but a reality model: a sandbox to explore what it means to be.

What I find most captivating isn’t just what Life can do, but what it represents. It shows us that simplicity doesn’t mean shallowness. That determinism doesn’t preclude wonder. That from rule-bound systems, agency—apparent or real—can emerge. Life is a reminder that maybe, just maybe, the universe we inhabit follows similar principles: a few core rules, infinite manifestation.

A Personal Note: Reverence for Conway

As someone fascinated by emergence, system dynamics, and the blurry line between art and science, I hold John Conway in something close to spiritual esteem. Not because he built a complex machine, but because he trusted simplicity. He believed that beautiful things could arise from unadorned truths. And he was right.

There’s an almost sacred feeling when observing a glider sliding diagonally through an empty field—its purpose, if any, unknown. Or when watching a breeder release streams of logic-bearing entities into the void. It is, in its way, creation. Not unlike observing life itself: patterned, fragile, evolving.

The Future of Life

Where might this all go? With the rise of AI-assisted pattern discovery, Life is evolving faster than ever. We are uncovering new types of “organisms”—patterns that defy expectation and hint at entire classes of behavior we haven’t categorized yet.

Could Life become a platform for digital ecologies? Could it evolve in tandem with artificial intelligence to explore fundamental questions of existence? Could it inspire new programming languages, or even hardware architectures modeled on emergent behavior?

It’s possible. And even if none of these things come to pass, Life will continue to be what it has always been: a quiet miracle of pattern and potential. A universe with four laws. A canvas for anyone curious enough to press play and watch.

The Simulation Within the Simulation

As the screen zooms out, as gliders continue their slow march across an endless grid, a question lingers—silent and terrifying in its simplicity:

What if we are them?

What if our consciousness, our world, our universe… is merely a larger instance of Life? What if we are patterns—running on rules we cannot see, evolving in a space we cannot touch, sustained by a computation too vast to perceive?

Perhaps our laws of physics are just rules—our causality, a neighbor function. Perhaps the emergence of thought, society, beauty, and pain are nothing more than gliders, oscillating through time. Life becomes more than metaphor—it becomes mirror.

John Conway gave us four rules and a blank canvas. What if we’ve been living inside someone else’s canvas all along?

Conway may be gone, but Life goes on.